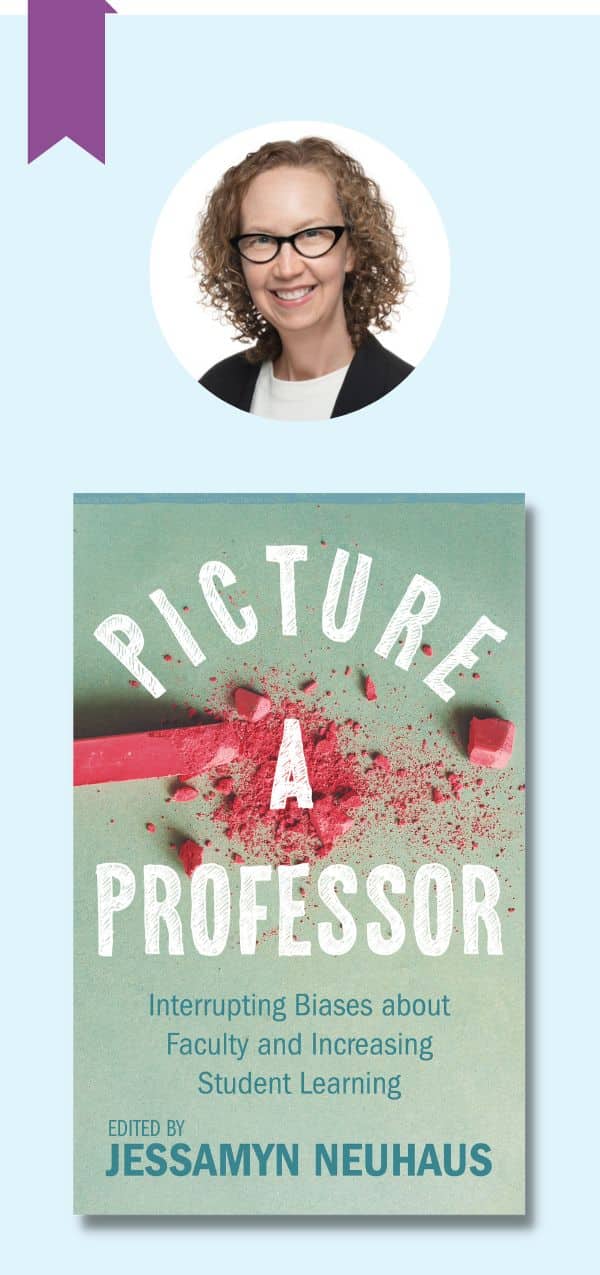

‘Picture a Professor’: An Interview With Jessamyn Neuhaus

James M. Lang

Jessamyn Neuhaus

We were thrilled when Jessamyn Neuhaus proposed Picture a Professor: Interrupting Biases about Faculty and Increasing Student Learning for the Teaching and Learning Series at West Virginia University Press. She had previously authored Geeky Pedagogy, one of the most engaging reads in the series, and we knew that she would give this important topic the attention it deserved. She took on the arduous task of assembling an edited collection during a very challenging time in higher education. The finished book reflects her commitment to highlighting the diverse voices who are pushing the scholarship of teaching and learning into welcome new directions. Both the interview and excerpt below will give readers a sense of Neuhaus’ mission-driven approach to this work, and I hope that the book will introduce readers to many authors whose work can inform our evolving thinking and practice in higher education.

James M. Lang, Ph.D.

The interview

1. You have created a narrated presentation for OneHE on the myth of the “Super Teacher,” so I’ll borrow a phrase from superhero mythology: Tell me the origin story of Picture of a Professor.

Picture a Professor began with a snarky voice in my head. When I was doing a deep dive into the scholarship of teaching and learning (SoTL) for my book Geeky Pedagogy: A Guide for Intellectuals, Introverts, and Nerds Who Want to Be Effective Teachers (West Virginia University Press, 2019), I began noticing how frequently otherwise excellent scholarship of teaching and learning failed to address the realities of embodied identity and systemic discrimination in higher education. I would read an article about “best practices” or a book about what all “excellent college teachers” do, and there would be no mention of what sociologist Roxanna Harlow termed “disparate teaching realities” in higher education—the way that identity markers, employment status, student population, and other specificities of our individual teaching context create unequal levels of teaching labor.

It’s just a fact that our educational institutions are shot through with systemic racism, sexism, ableism, and other forms of discrimination. Our embodied identity is therefore not a footnote to our teaching practices, as too much SoTL seems to suggest, but rather sits squarely in the center of how students perceive and interact with us, and what we must do in order to effectively facilitate student learning. To be clear, there is abundant research, going back decades, that offers compelling evidence of the multiple ways that racial hierarchies, gender ideology, and a wide variety of intersectional inequities impact higher education generally and college teaching specifically. But SoTL (with the notable exception of work focused on how these inequities influence student evaluations of teaching) has been slower to demonstrate that any teaching advice or study of effective learning must take into account our disparate teaching realities.

The snarky voice in my head began sarcastically commenting more and more frequently. I’d be sitting there trying to read, and The Voice was all: “Oh, okay, sure, let’s just pretend that our classroom is an enchanted bubble floating high above the dreary workaday world below. In this wondrous place of perfect equality and justice, there’s no racism or sexism or discrimination of any kind. Students and teachers alike gather as purely intellectual beings seeking truth and knowledge, completely free of biases and preconceptions about one another. The sky is always filled with rainbows and every morning we ride our very own pet unicorn down Lollipop Lane to another glorious day of tenure, teaching eager students hungry for learning.”

I needed to stop snarking and do something. That something was Picture a Professor.

2. How did you identify the contributors whose essays appear in the book?

I put out a public Call for Papers (CFP) and also directly contacted potential contributors through the professional network I’ve established primarily through Twitter but also through teaching conferences and educational developer organizations. I received far more submissions than I could include, and it was not easy choosing the final chapters. In fact, I had originally planned to include a chapter in the book written by me about how to contend with student evaluations of teaching, but in the end, decided to make that a bonus chapter (available online at https://pictureaprofessor.com) instead so there was more room to include other voices in the published collection. I was fortunate to get so many submissions that it was not difficult to put together a collection authored by a true diversity of instructors—not just in terms of personal identity but also people working in a variety of disciplines and at different stages of their careers with different approaches to SoTL.

The criteria I used to assess their chapters was very similar to the overarching goals of the West Virginia University Press series, “Teaching and Learning in Higher Education:” Evidence-based and actionable teaching advice applicable in a variety of contexts, written “by human beings.” In other words, highly readable (the CFP said I was looking for “short and snappy”) and practical SoTL. I chose contributors who met this imperative, and who sought to empower and inspire instructors while at the same time acknowledging and directly addressing disparate teaching realities. These authors strike an amazing balance between deep and abiding trust in the transformative power of education and of all students’ ability to learn and grow, while at the same time fully recognizing intersectional systemic discrimination in higher education that creates teaching inequities, including student biases and preconceptions about faculty.

3. Putting together an edited collection demands a ton of logistical work—working with contributors, managing deadlines, editing essays. What was that process like for you? Bonus if you have any advice for others who might wish to take up that work.

My #1 piece of advice is don’t try to do this during multiple overlapping global, national, and local health, political, and cultural crises! When the covid-19 pandemic hit, I seriously considered postponing the project indefinitely. But then that sarcastic, snarky voice (see Question #1) piped up, saying “Yeah, sure, no problem, we can totally wait until it’s a more pleasant, convenient time to help instructors counteract student biases about faculty. No need to rush these things. I’m sure nobody, right this minute, is struggling, discouraged, and starting to doubt their own teaching efficacy because of how systemic racism, sexism, all the isms, impact teaching.” So I plowed ahead. And I found that the contributors seemed to share my feeling that even though it was an extraordinarily difficult time to complete, well, anything at all, there was a pressing need to get the book done and into our readers’ hand. In fact, for me editing this book was kind of a lifeline during the worst of the pandemic era upheavals—a source of inspiration and connection to other like-minded teacher-scholars.

The other thing I had going for me is that I truly love collaboration, and editing felt very much like a collaborative writing project. SoTL tends to attract people who are open to collaboration and these contributors were all very open to suggestions for revisions. We had some highly productive, engaging conversations about how to make each chapter and the book itself the strongest piece of writing it could be.

One final practical note about editing a book: I’d recommend soliciting complete chapters, not proposals. Not only did it help me choose the contributors, but it gave all of us a significant head start on the revisions process.

5. Can you give me three things you learned about teaching and working in higher education in the course of editing this book?

It wasn’t so much a matter of learning brand new information as having a bunch of ideas clarified and confirmed. First, I learned more about my own positionality as a tenured, able-bodied, White, cisgendered woman teaching in the humanities. The process of collecting, editing, and publishing also made me reflect on and see more clearly those aspects of power I have as an established scholar in the field. As someone deeply opposed to self-important unnecessary gatekeeping endemic to academia, I had to do some serious thinking about what it meant to be a senior scholar literally choosing who would be included in this volume. And predictably, I learned more about how the specific systemic biases and discrimination faced by anyone in the academy who doesn’t “look like” a professor—meaning, anyone who isn’t a White man (tweed jacket with elbow patches optional but highly encouraged)—play out in the classroom. For instance, it shed new light for me on how routinely women teaching in STEM fields encounter students’ skepticism about their disciplinary expertise.

Second, I learned at a whole new level that inclusive pedagogical, research, and writing practices are an ongoing endeavor. I’ve always argued that effective teaching is an ongoing endeavor, that every instructor in every context, from their first class to their last, is always learning how to be an effective teacher. But editing Picture a Professor brought home to me how this applies to inclusive, equity-minded scholarship and teaching as well. For example, working with authors Sheri Wells-Jensen, Emily K. Michael, and Mona Minkara, who wrote the chapter “How Blind Professors Win the Day: Setting Ourselves Up for Success,” and getting their input on a draft of my Introduction, made me realize the ableist way that I’d used the word “blind” as a pejorative term in my previous writings. Emily K. Michael, a poet, pointed out later that language is complex and “slippery” so it’s vital that we all keep learning about how to use it inclusively and effectively. As contributor Donna Mejia encourages her students to remember, we need to embrace the task of “fumbling forward” when it comes to equity and inclusivity in our professional and pedagogical practices. When, not if but when we make mistakes, what matters is that we keep learning and moving forward.

Third, working with these authors powerfully reinforced my understanding of how important it is in academia to build supportive personal pedagogical learning networks and in the words of contributor Celeste Atkins, to “find your people.” Before editing this book, I was well aware that the best SoTL and college teaching advice conveys the message that “you are not alone.” But the Picture a Professor authors made me realize in new ways how isolating teaching in higher education can be. A vital first step in empowering instructors’ pedagogical self-efficacy in the face of disparate teaching realities is showing faculty that they are not alone in the challenges and complexities of navigating those inequities while facilitating student learning.

6. How can readers can get touch with you? Are you available on social media, and are you available for virtual or on-campus speaking engagements?

Currently, my most important professional and pedagogical personal learning network is on Twitter @GeekyPedagogy and I’m going to fight tooth and nail to stay there. I always enjoy doing workshops and keynotes on a variety of topics, in person and online. Readers can find more information at https://geekypedagogy.com.

Excerpt from the book

Look! Up at the lectern!

Is it a teacher? Is it an educator? No, it’s . . . Super Professor!

More charismatic than a Hollywood heartthrob! Able to win over the most reluctant, resistant student with a single quip or impactful PowerPoint slide!

During class, Super Professor delivers Oscar-worthy performances, scribbling formulas theatrically on a chalkboard or eloquently reciting lyric poetry to entranced students agog at the expertise on display. Super Professor always lectures brilliantly and entertainingly, effortlessly elucidating the most obscure subject. Students hang on Super Professor’s every spellbinding word, laughing at each joke and painlessly absorbing difficult academic material simply by listening to Super Professor talk about it. Students are routinely so overcome by admiration for Super Professor’s lectures that they spontaneously burst into applause.

Super Professor appears over and over again on our TV and movie screens, quite wrongly depicting learning as a purely top-down activity whereby knowledge is simply poured into students’ heads by an irrefutable expert. He’s also usually an able-bodied, cisgendered, heterosexual White man. In this way, popular culture reflects and reinforces the myriad of political, social, and cultural discourses that gender intellectual authority as male and support what Resmaa Menakem terms “white-body supremacy” by racializing knowledge and expertise as White. Socialized and enculturated by this imagery, all too often, Super Professor is who we think of when we picture a professor.

Every single person teaching a college class in any subject or modality must contend in some way with the narrowly defined, limited/limiting expectations of how a college professor should act in the classroom, what they should look like, and what identity markers they should embody. Anyone who doesn’t manifest those traits—before saying a single word or interacting in any way with students—will not meet certain conscious and unconscious student expectations. And expectations shape learning. Moreover, biases about professors impact students’ ability to connect and build rapport with instructors and to fully engage in the course material. Picture a Professor takes as its starting point that the “socially imagined professor,” as contributor Rebecca Scott terms it in her chapter, impedes effective teaching and learning.

Assumptions about what professors “look like” directly contribute to what sociologist Roxanna Harlow identifies as “disparate teaching realities.” White women, women faculty of color, faculty with physical disabilities, non-binary faculty, and all Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) faculty must navigate different intersectional mazes of racial, gender, and other biases about embodied identity on an exhausting daily basis. Scholar of higher education Nichole Margarita Garcia explains that no matter what their intention, when students, colleagues, administrators, staff, or random strangers tell her “you don’t look like a professor,” the phrase is a verbal assault on her expertise and her academic authority. It’s a manifestation of racial hierarchies and systemic inequities in higher education, including white-body supremacy, because anyone who doesn’t “look like” a professor is “presumed incompetent,” in the unforgettable words of that trailblazing edited collection and its 2020 follow-up volume.

“Before we even open our mouths,” as contributors Jacinta Yanders and Ashley JoEtta write in their chapter, students question the very presence of any instructor who doesn’t conform to the professor stereotype. Similarly, in their chapter about teaching as blind/seeing impaired professors, contributors Sheri Wells-Jensen, Emily K. Michael, and Mona Minkara summarize this deep-seated student skepticism: “What they want to know is whether we belong in the classroom.” Importantly, such implicit or even explicit questioning, and instructors’ subsequent feeling of “unbelonging,” as contributor Jesica Siham Fernández terms it in her chapter, is never restricted just to the classroom. Ableism, sexism, ageism, racism, homophobia and heterosexism, transphobia, classism, and other systemic inequities are baked into all aspects of academia—inequities that are further exacerbated by higher education’s exploitative contingent and non-tenure-track employment practices.

A wide range of scholarly books and articles, research studies, memoirs, and social media extensively documents these inequities and shows how prejudices manifest in different scholarly disciplines in different ways, such as additional biases against all women faculty in the STEM fields. The sexism and racism of academic systems are particularly evident when it comes to student evaluations of teaching and the disproportionate power these evaluations hold over professional teaching careers. However, published scholarship of teaching and learning (SoTL) and popular advice about college classroom management, learning assessment, and other teaching stratagems frequently fails to adequately address or even acknowledge this simple truth: embodied identity matters to college teaching and learning. As I’ve argued elsewhere, disparate teaching conditions are one of the very first realities of teaching and learning both in person and online that every SoTL book, article, and Chronicle of Higher Education advice column should acknowledge.

SoTL needs to much more thoroughly and methodically grapple with all the ways that society and academia’s systemic inequities and hierarchies traverse our individual classrooms and to better address the “implicit professor theory” described in contributor Reba Wissner’s chapter. As contributor Chavella T. Pittman states in her chapter, “It is impossible to understand the best teaching practices without understanding their intersection with the bodies that are doing the teaching and learning.” More scholars of teaching and learning need to offer actionable pedagogical approaches that recognize the significance of embodied identity and propose real-life teaching strategies—tools, means, activities, methods, and processes—for empowering a true plurality of professors in their teaching practices. This is the aim of Picture a Professor.

For discussion

In the interview, Jessamyn Neuhaus argues that “identity markers, employment status, student population, and other specificities of our individual teaching context create unequal levels of teaching labor.” How have you experienced or observed this dynamic playing out at your institution or in your career? What is “creating unequal levels of teaching labor” in your life or the lives of your colleagues?