Click here to view the video transcript

The Framework for Information Literacy was developed by the Association of College and Research Libraries or ACRL in 2015 as a way to articulate core concepts and ideas underpinning the practice of information literacy. Previous to the Framework’s development, librarians used a set of standards similar to learning outcomes to structure their information literacy teaching. As academic librarians became more deeply involved in teaching and learning, they realized that the set of skills outlined in the standards was only touching the surface of what they had been teaching.

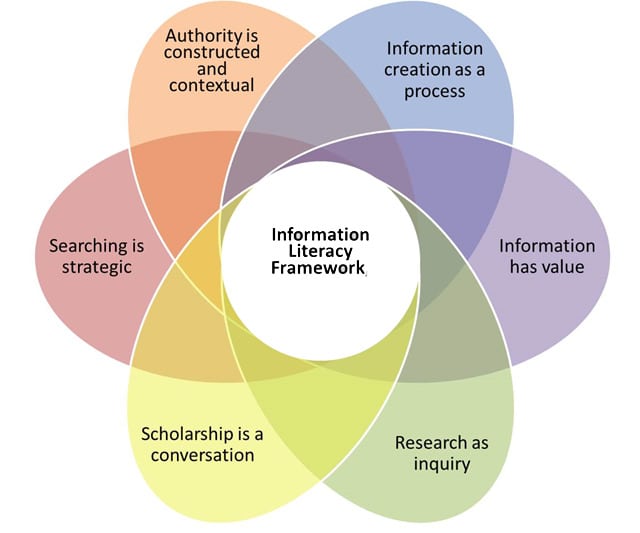

The Framework came about as a way to make those underlying concepts more tangible so that both librarians and course instructors could structure their teaching in a more intentional way. The Framework identifies a set of larger essential understandings or thresholds for learners about information sources and research processes. These essential concepts provide the scaffolding for learners to expand their information contexts, to engage in inquiry more productively, and to become more independent in their investigation. These concepts are embodied by six frames, which Craig will discuss next.

The Framework for Information Literacy is an overarching structure for showing how the big ideas in information literacy are related to each other and how they provide a pathway for students to understand the information ecosystem in a deeper way. There are six of these frames. The first one is Authority Is Constructed and Contextual, and the gist of that idea is that authority is not just unidimensional, that it’s variable, depending on the context, who needs particular kinds of information, who would be considered authoritative or credible, and developing information and sharing it with the world.

The second big idea is Information Creation as a Process, and this is really about the lifecycle of information, when it originates, how it might be produced and shared through different means and different containers of information over time. It’s intended to convey a message originally, and that message may change or shift depending on the container or the means of distribution.

The third big idea is Information Has Value, and that particularly relates to the legal and economic aspects of information, but that’s one dimension of value. Information value can also be understood as an internal one in which the user, the student, or the scholar, depending on their own culture or their own worldviews or perspectives or other aspects of identity, may value an information source in different ways

The fourth big idea is Research as Inquiry, and that speaks to the aspect that research is not linear, that research questions that any scholar or researcher begins with are often iterative and refined over time as a result of what the investigator or the inquirer finds. So this is a challenging idea for students to learn that they must be able to refine questions. An initial question will only be the starting point for them.

The fifth big idea is Scholarship is Conversation, and that really provides an explanation of how researchers and scholars relate to each other, how they have debates and conversations in the literature in their fields over time, and how those debates are important to know about, rather than looking at just isolated pieces of information, isolated articles, isolated books, that students may hone in on but not understand the larger context.

Then the last big idea is Searching as Strategic Exploration, and this really speaks to the need for students to develop a metacognitive mindset, that is, to monitor their own searching and not foreclose or foreshorten what they are looking at, but to think more strategically about the whole information ecosystem. So it’s really about developing a cognitive map of the whole information ecosystem in a way that goes along with the Research as Inquiry frame that they are also learning.

The Framework for Information Literacy was developed by the Association of College and Research Libraries (ACRL) in 2015 as a way to articulate the core concepts and ideas underpinning the practice of information literacy.

Before the Framework’s development, librarians used a set of standards similar to learning outcomes to structure their information literacy teaching. As academic librarians became more deeply involved in teaching and learning, they realized that the set of skills outlined by the Standards was only touching the surface of what they had been teaching. The Framework came about as a way to make those underlying concepts more tangible so that both librarians and course instructors could structure their teaching in a more intentional way.

The Framework identifies a set of larger essential understandings, or thresholds, for learners about information sources and research processes. These essential concepts provide the scaffolding for learners to expand their information contexts, to engage in inquiry more productively, and to become more independent in their investigations.

The six essential understandings in the Framework for Information Literacy are:

- Authority is constructed and contextual

- Information creation is a process

- Information has value

- Research as inquiry

- Scholarship is a conversation

- Searching is strategic exploration

Each of these concepts is called a “frame” (hence the overarching “Framework”).

Let’s consider the Scholarship as Conversation frame. It is meant to build learners’ understanding that scholars and researchers engage in dialogue, debate, disagreement, and testing of theories and hypotheses, over time. Because a sense of conversation among scholars and schools of thought within which they conduct research is often missing in novice approaches to information, this frame can be used to build lessons, assignments, and even parts of courses to provide a context for students to explore how scholarly sources are “in conversation” with each other. Exploring this idea of conversation unearths connections between ideas and the people writing about them. This concept also complicates the beliefs that all scholarly sources represent uncontested fact, or that one study or scholarly source “proves” the researcher’s point. It also helps to show how scholarship is growing and evolving, is impacted by the work of others, and that understandings change over time with new evidence.

The concept of scholarly conversation can also provide a foundation for understanding scientific consensus. In the “Understanding Science” model from the University of California – Berkeley (see the PDF below), a key component of the scientific process is presented as “Community Analysis and Feedback”, which frames the processes of feedback, peer review, and discussion with colleagues as scholarly conversation, taking place not just in person but through publication, replication and dissemination.

Intentionally framing this process as a conversation can help learners understand individual scholarly articles as living pieces of a broader community that do not exist in isolation. The idea of consensus implies agreement among members of a larger community based on shared knowledge and evidence, which provides a direct counterpoint to novice conceptions such as “one scholarly article says it so it’s true” or the false equivalence of an outlier article or group outweighing the majority consensus simply by its existence.

Discussions

In what ways have you noticed that a sense of the scholarly conversation, or the context in which information sources build on and respond to other sources, might be missing from your students’ work? Conversely, in what ways have you seen students demonstrate an understanding of scholarship as a conversation?

Please share your thoughts and questions in the comments section below.