Click here to view the video transcript

A few years ago, I did some research on what motivates students to complete homework. The students were in an undergraduate class I was teaching at the time, and homework was not compulsory. I found out that none of the 18 students in the study completed homework because they were intrinsically motivated. That’s not surprising, right? Through analysing students’ homework logs and by interviewing them, I found out that one, students engaged in homework which they perceived as important in contributing to their academic studies. This type of homework explicitly made connections to what they were learning in class. Two, students engaged in homework that they found to be intellectually challenging. Simple tasks that ask students to just copy and paste answers were not recognised as academically valuable. Students wanted tasks that asked them to think critically, that challenged them. Three, homework that scaffolded learning by providing models, grids, templates, and other types of guidance were perceived as valuable and improved students’ confidence and sense of competence in engaging with academic content. So overall, students’ identification with the value of homework led to their exercise or of a relatively high degree of autonomy in engaging with it.

Now, in another study with a different group of students, a different group of undergraduate students, I looked at what kinds of naturally-occurring contexts and resources do students engage with out of class. I found that many students use popular culture to assist their learning. They recognise naturally-occurring online resources, in particular YouTube and websites, as legitimate ways of learning. These students did not simply passively view content in these media, but were strategic in their utilisation. They created tasks for themselves to complete as they interacted with the resource. The educator had no role in students’ decisions to engage with these resources for learning purposes. Instead, the students identified their needs and goals and took initiative. The students were in charge of their learning out of class. Again, students’ perceptions of the value and the significance of the out-of-class learning experience is what prompted them to engage with it.

Our knowledge of what motivation entails is crucial in creating teaching practices that promote learner autonomy beyond the classroom.

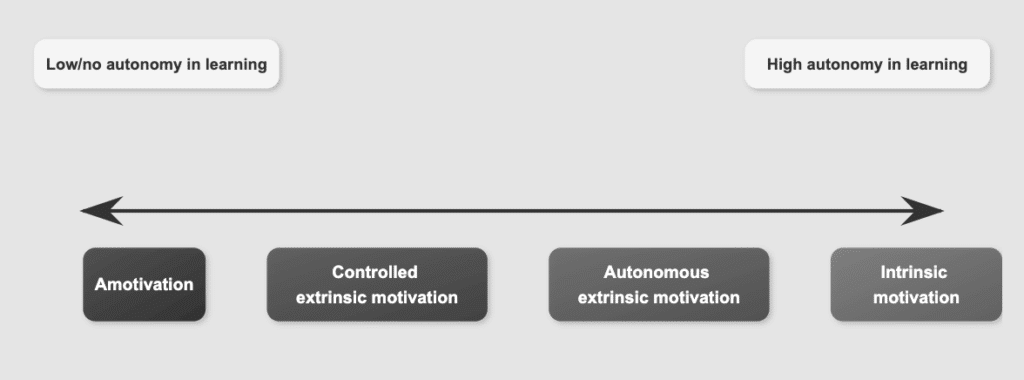

We should think of motivation as a continuum:

Image description: A horizontal spectrum showing the progression of learning autonomy from left (low/no autonomy) to right (high autonomy). The spectrum includes four stages: Amotivation on the far left, followed by Controlled extrinsic motivation, then Autonomous extrinsic motivation, and finally Intrinsic motivation on the far right.

On one end we have amotivation, which is the student not engaging in learning out-of-class. On the other end of the continuum is intrinsic motivation, where the student is inherently and genuinely interested in learning out-of-class and self-regulates the contexts and resources they engage in. For instance, a student might genuinely enjoy doing homework, or a student might enjoy listening to a particular video channel that explains the subject matter they are studying. The student engages in out-of-class learning because of the satisfaction and joy the experience gives to the student.

In between amotivation and intrinsic motivation, we have different types of extrinsic motivation that drive out-of-class learning. Students engage in out-of-class learning to meet an external reward or outcome. Extrinsic motivation is often seen as an unwanted attribute in a student. However, as Edward Deci and Richard Ryan argue, students learn for a variety of reasons, many of which are not related to inherent self-satisfaction, but which equally create positive and rewarding learning experiences. It’s also unrealistic to expect that students are all intrinsically interested in what they are studying. The reasons they do so are complicated and many.

Extrinsic motivation can be autonomous. Let’s look at two examples.

EXAMPLE 1: When a student engages in out-of-class learning to obtain a reward, satisfy an external demand or avoid punishment, the activity is controlled by factors external to the activity itself. An example is a student who completes homework to receive a mark. This is a highly externally controlled form of motivation. The student takes the initiative to engage in out-of-class learning but the impetus is not necessarily to meet learning goals or needs and they may or may not monitor their learning.

EXAMPLE 2: A more autonomous form of extrinsic motivation is when the student recognises out-of-class learning as personally, academically, or socially important. For instance, a student completes an out-of-class revision quiz because they recognise the knowledge gained in the quiz is necessary to understand the next section of academic content or they believe knowing the content in the quiz is necessary to become successful in their chosen future profession. They are not intrinsically motivated, but their out-of-class learning is self-determined – they have identified a learning need and goal, taken action and can monitor and self-evaluate their learning. This type of motivation is more likely to develop lifelong learning behaviours in students.

Kocatepe, M. (2017). Extrinsically motivated homework behaviour: Student voices from the Arabian Gulf. In J. Kemp (Ed). Proceedings of the 2015 BALEAP conference (pp. 97-106). Garnet Publishing.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations: Classic definitions and new directions. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25(1), 54–67.

Ryan, R. M. and Deci, E. L. (2002). Overview of self-determination theory: An organismic dialectical perspective. In E. L. Deci and R. M. Ryan (Eds.), Handbook of self-determination research (pp. 3–33). University of Rochester Press.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2020). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation from a self-determination theory perspective: Definitions, theory, practices, and future directions. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 61, 101860.

Discussions

How do you motivate your students to engage in out-of-class learning? What strategies work well? What don’t?

Please share your thoughts and questions in the comments section below.