Click here to view the video transcript

Information literacy research has built up over decades as a result of the work of individual practitioners, individual educators, faculty, and library and information science, and in related fields such as media studies, communications, and particularly though what we have learned from Project Information Literacy, which is a major research think tank that has examined the research practices of students for decades, we have learned that students lack context for understanding the information ecosystem. They do not know where to begin. They are at a loss, and they are often satisficing with what they find.

There was an important conference paper given at the 2013 Association of College and Research Library Conference by Alison Head, which identified these two key findings. First, that students do not know how to formulate a good research question, and second, when they find information as a result of the satisficing process, they do not know how it fits within the larger flow or context of information, how it’s produced, how it’s created, how it’s documented, and how it’s shared with others. Those are the two most important key findings I think that have persisted for us even into this era where we are now dealing with the challenges of artificial intelligence.

The primary research findings come from Project Information Literacy and other researchers in Library and Information Science, Communications, and related fields. One of the key findings of research on learners’ gaps in understanding the landscape of information sources is lack of context. Learners can too often be satisfied with a few websites, articles, blog posts, or YouTube videos without considering how each is produced and how they might fit together into a kind of ecosystem of information. Other key findings include: novice learners struggle to formulate effective research questions within a specific context; often approach research as a linear process of “finding answers” rather than an open-ended process of investigation; struggle with recognizing authoritative sources in disciplinary contexts, and do not yet identify as responsible creators of information artefacts rather than only consumers of information. These less nuanced approaches are sometimes reinforced through the use of tools such as checklists to determine “good and bad” sources, previous admonitions to avoid Wikipedia, and favoring .org or .edu sites as authoritative, to name a few.

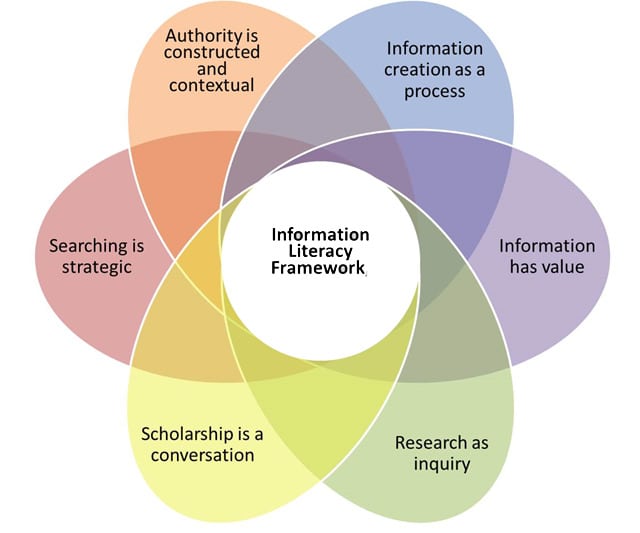

The Association of College and Research Libraries (ACRL) Framework for Information Literacy uses the threshold concept theory to address the shift from these more simplistic approaches to information and research to nuanced, contextual approaches.

Based on the work of Meyer and Land (2003), “threshold concepts are the core ideas and processes in any discipline that define the discipline, but that are so ingrained that they often go unspoken or unrecognized by practitioners (Hofer et at, 2012). When instructors can identify specific places where students struggle with information and research processes, tacit (or unspoken) concepts that are second nature for experienced researchers can be brought to light and explicitly addressed.

An example of ways that an information literacy threshold concept can promote more nuanced approaches to research would be to consider the concept “Research as Inquiry.” A novice researcher might view ‘research’ as merely a fact-finding mission aimed at compiling a report that summarises information already known and readily available. This may very well have been their learned experience of research writing at this point. With this particular purpose in mind, a researcher would naturally prioritize seeking out the most “accurate” or “reliable” facts about their topic. Research as inquiry approach, however, encourages the researcher to move beyond initial fact-finding to ask questions, pursue new lines of thought, and develop and explore original ideas through interacting with sources. This type of research can be unsettling for a learner who is used to a reporting approach as it asks them to incorporate uncertainty and original thought, running the risk of not having the “correct answer”. It is a threshold, however, that is essential for a novice researcher to cross in order to progress toward expertise in their field.

- Head, A. (2013). Project Information Literacy: What Can Be Learned About the Information-Seeking Behavior of Today's College Students? Invited Paper, Association of College and Research Librarians Conference, Forthcoming.

- Hofer, A. R., Townsend, L., & Brunetti, K. (2012). Troublesome Concepts and Information Literacy: Investigating Threshold Concepts for IL Instruction. Portal: Libraries & the Academy, 12(4), 387–405.

- Meyer, J., Land, R., (2003). Threshold Concepts and Troublesome Knowledge: Linkages to Ways of Thinking and Practising Within the Disciplines. ETL Project - Occasional Report 4 (Edinburgh: Enhancing Teaching-Learning Environments in Undergraduate Courses Project)

Discussions

What do you see in your students’ information-seeking habits that confirm (or differ) from these research findings from Project Information Literacy?

Please share your thoughts and questions in the comments section below.