Learning out-of-class is a manifestation of learner autonomy.

Autonomy refers to the capacity to act with volition and take charge of one’s learning. An autonomous learner recognises potential learning opportunities and utilises them. Equally important, an autonomous learner can recognise constraints to their learning imposed by contexts or resources and adjust and undertake alternative learning paths. An autonomous learner, therefore, self-governs their worlds of learning. Autonomy is not a universal construct; it can vary from one person to another as well as within the same person. The capacity to exercise autonomy is what is universal.

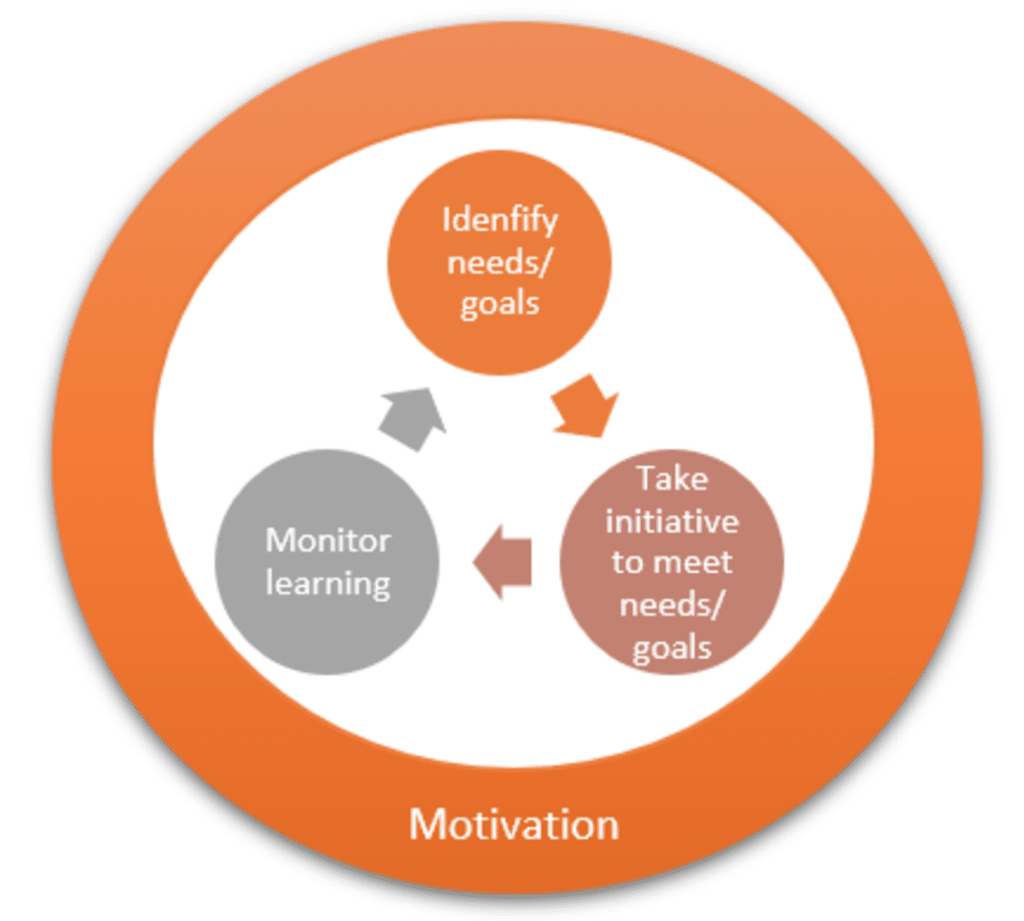

The diagram below illustrates how a student exercises autonomy when learning beyond the classroom:

Diagram Description: A circular diagram illustrating the cycle of learning, surrounded by an outer orange ring labeled ‘Motivation.’ Inside the circle are three interconnected elements: (1) ‘Identify needs/goals’ (top, in orange), (2) ‘Take initiative to meet needs/goals’ (right, in orange), and (3) ‘Monitor learning’ (left, in grey). Arrows connect these three elements, indicating a continuous process.

Let’s have a closer look at this in the video below.

Click here to view the video transcript

Phil Benson in his book, “Teaching and Researching Autonomy” identifies three stages of out of class autonomous behaviour. First, a student who is autonomous out of class identifies learning needs and sets goals. Needs and goals may or may not be intentionally or formally identified. For example, you might have given a student feedback on an assignment and made a set of recommendations for how they improve it. In this case, you have assisted the student in identifying their needs and you’ve given them direction in how they meet them. Alternatively, a student might recognise they struggle with understanding a particular concept. They might search for the resources that they believe will help them address this issue. In this case, the student has identified a need and a goal.

Second, the student takes initiative to meet their learning needs and goals. They transform contexts and resources into learning opportunities. For example, a student might download and use an educational resource available on the learning management system or a student might reach out to classmates on social media and ask to form a study group. If a student perceives a resource as irrelevant or as insignificant in meeting their needs, they may not actually engage with it. They may decide not to. An autonomous student will find an alternative resource that meets their learning needs and goals.

The next step is the student monitors their learning. An autonomous student will recognise to what extent the contexts and resources they are engaging with out of class are effective, and they will make necessary changes if necessary. For example, a student might realise that a teacher’s recommendation to use a referencing handout isn’t actually assisting them in learning accurate referencing, so instead, they might choose to use referencing software. The student realises that the software better meets their learning need. As the student monitors their learning, they revise learning needs and goals. They take further actions, and they develop other learning needs and goals. All these actions that make up autonomous out of class learning are underpinned by motivation. Identifying goals, taking initiative, and monitoring learning are derived from the motive to learn out of class. The motive can be intrinsically driven, or it can be to meet external incentives.

Benson, P. (2011). Teaching and Researching: Autonomy in Language Learning. (2nd ed.). Routledge.

Shunk, D. H., & Greene, J. A. (Eds.). (2017). Handbook of self-regulation of learning and performance (2nd ed.). Routledge.

Discussions

How do you help students become more independent in identifying their learning needs?

Please share your thoughts and questions in the comments section below.